International Perspectives

Education in Netherlands

Education is compulsory in the Netherlands between the ages

of the ages of 5 and 16. The instruction language is Dutch, but more and more

schools and universities teach in English. Children in the Netherlands get 8

years of primary education, 4, 5 or 6 years of secondary education (depending

on the type of school).

What are the Netherlands doing successfully?

1.

Schools in the Netherlands give homework in

small quantities. Whereas in the USA they are known to give more than the recommended

amount of homework to their students which is time consuming. Research has

shown that play and exercise are vital to children’s growth and school performance

hence why schools in Netherlands give homework to their pupils sparingly. Dutch

students under the age of 10 receive very little homework which gives time for daily

exercise.

22. Education in the Netherlands is affordable. Primary

and secondary education is free; parents need to pay for annual tuition ONLY

after the child turns 16 years old and low-income families can apply for grants

and loans (as the UK allows for university at age 18). For university students,

the average cost of button is about $2000 per year; in the USA it is close to $10,000

which is a significant amount of money for education.

33. There are different types of classes Dutch students

can take for secondary school before they attend college. Students can take

HAVO (senior general secondary education) or VWO (pre-university education) before

they go to college. They can also take VMBO (preparatory secondary vocational

education) this course is if they do want to attend college right away. This system

allowed students to work with a program that will accommodate their needs.

44. Education in the Netherlands involves learning a

second language. While American students usually start learning a second

language in middle school or high school, some primary schools in the

Netherlands teach English as early as group 1m which is the equivalent of

American kindergarten or UK nursery. (which Welsh schools tend to teach Welsh in

nursery). All Dutch students learn English, but some schools require students

to learn an additional language. There are even bilingual schools for every

education level, where some classes are taught in English and others are taught

in Dutch.

55. Dutch school week is different from American school

week and UK school week. A school day in primary school usually takes place

from 8:30am-3:00pm on weekdays, but students go home for lunch instead of

eating at the school canteen. On Wednesdays, schools dismiss students around

noon. – this allows children to have a break from school and return with a

clear mind set readying them to learn.

Education in Singapore

The Singapore education system. Pre-school is offered from

age 3, in Singapore, with primary schooling from the age of around 7. After

primary school children move onto secondary school, which runs for students

ages from around 12, to 16 or 17.

11. In 2015, the Organisation for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD) rates Singapore as having the ‘best

education system in the world’. OECD director Andreas Schleicher says that

students in Singapore are especially proficient in maths and the sciences. In English,

the average Singaporean 15-year-old student is 10 months ahead of students in

westerns countries and 20 months ahead in maths. Singaporean students also score

among the best in the world on international exams.

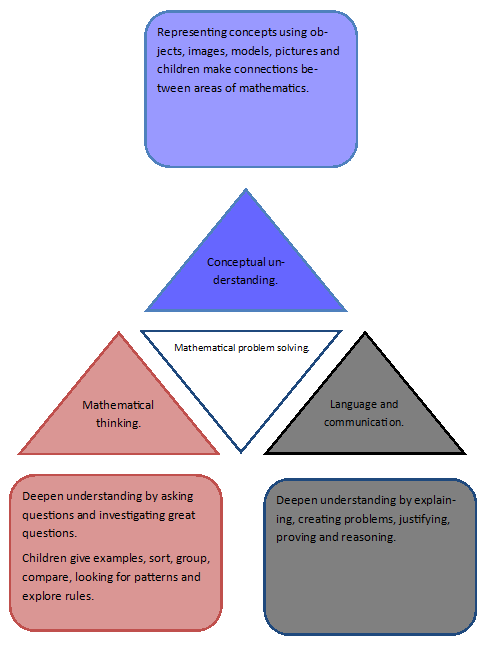

22. Education in Singapore is superior because the

classes are forced on teaching the students specific problems solving skills

and subjects. The classroom is highly scripted, and the curriculum is focused on

teaching students’ practical skills that will help them solve problems in the

real world. Exams are extremely important, and classes are tightly oriented around

them.

Education USA

Prior to higher education, American students attend primary

and secondary school for a combined total of 12 years. Around age 6, U.S.

children begin primary school, which is most commonly called ‘elementary

school.’ They attend 5 or 6 years and then go onto secondary school.

11. American students attend primary and secondary

school for a combined total of 12 years. These are referred to as the first through

twelfth grades.

22. Around age 6, U.S. children begin primary school,

which is commonly called ‘elementary school’. They attend 5 or 6 years and then

go onto secondary school.

33. Secondary school consists of two programmes; the

first is ‘middle school’ and the second is ‘high school’. A diploma or

certificate is awarded upon graduation from high school. After graduating. Students

may go onto college or university which is known as ‘high education’.

44. U.S. high education costs around $14,300 per

year depending on the college or university. The US differentiates between

in-state tuition fees and out-of-state tuition fees, as well as between private

and public universities. These distinctions determine the tuition fee. The average

tuition fee for public two-year institutions is around £3000 per tear. While the

average fee for private four-year institutions is around $29,000 per year. Some

private four-year institutions can cost up to $50,000 per year. Loans are available

for students to be able to fund their education.

Education in the UK

UK education system. The education system in the UK is

divided into 4 main parts, primary education, secondary education, further

education and higher education. Children in the UK must legally attend primary

and secondary education which runs from about 5 years old until the student is

16 years old.

11. The UK education system is divided into four

main parts, primary education, secondary education, further education and

higher education. Children in the UK legally must attend primary and secondary

education which runs from 5 years old till 16 years old.

22. The education system in the UK also split into key

stages.

·

Key stage 1: 5-7 years old

·

Key stage 2: 7-11 years old

·

Key stage 3: 11-14 years old

·

Key stage 4: 14-16 years old

3 3. Students are assessed at the end of each stage. The

most important assessments occurs at age 16 when students pursue their GCSE’S.

Once students complete their GCSE’s they have the choice to go onto further education

or finish school and start working.

References

Nuffic https://www.nuffic.nl/en/subjects/education-in-the-netherlands/

(undated) (accessed on 09.07.19)

TransferWise https://transferwise.com/gb/blog/singaporean-education-overview

(undated) (accessed 09.07.19)

Study in the USA https://www.studyusa.com/en/a/58/understanding-the-american-education-system

(2018) (accessed 09.08.19)

Study in the UK https://www.internationalstudent.com/study_uk/education_system/

(undated) (accessed on 09.07.19)

Five Reasons Education in the Netherlands Works Well https://borgenproject.org/education-in-the-netherlands-work-well/

(2017) (accessed on 11.07.19)

Why Education in Singapore is so Good https://borgenproject.org/why-education-in-singapore-is-so-good/

(2017) (accessed on 11.07.19)

International student https://www.internationalstudent.com/study-abroad/guide/uk-usa-education-system/

(undated) (accessed on 11.07.19)

Understanding the American Education System https://www.studyusa.com/en/a/58/understanding-the-american-education-system

(2018) (accessed on 11.07.19)